BISFF2025|Correspondence 通信计划043:The Land of Wanting More 欲壑之邦

- 2025年11月17日

- 讀畢需時 10 分鐘

BISFF Correspondence 通信计划

This program involves conducting brief email interviews with the directors of the international films featured in the festival, in lieu of the traditional Q&A session that follows the screenings. Through this program, we hope to provide a platform for filmmakers to discuss their work and share their insights with our audience in China.

为了跨越种种障碍,开辟更多交流空间,我们设置了“BISFF Correspondence 通信计划”,对部分国际单元的参展作者进行系列访谈,这些访谈将在作品放映后发布在联展各个媒体平台。

The Land of Wanting More | 欲壑之邦

Marianna Rantou 玛丽安娜·兰图

2025 | 0:19:35 | Greece | Greek | Asian Premiere

Director: Marianna Rantou

Interviewer & Translator: Derek

Coordinator & Editor: Suliko

导演:玛丽安娜·兰图

采访、翻译:仲夏之门

统筹、编辑:苏丽珂

Q1:The phrase “wanting more” can hold variable meanings for women. Based on your creative practice and everyday interactions, what interpretation do you find most common or resonant?

A1:For me, wanting more means wanting more freedom, more tenderness, more truth. It’s the need for more space to breathe without fear, to live without constantly apologizing for our existence. It’s about wanting more opportunities — in life, in love, in work, in family, in friendship. It’s the longing to be seen and accepted as we are, to move through the world without shrinking, to not be afraid of how we are or who we might become. For many women I meet, this desire isn’t about excess — it’s about reclaiming the simple right to live expansively, with honesty and courage.

Q2:In the film, we see women of different ages and appearances — including those with disabilities and those nude — presenting their daily lives before the camera: talking, laughing, sleeping, bathing, masturbating, and so on. Are you acquainted with these participants? How did they become involved in the project? And how did you build the trust that allowed them to behave naturally while facing the camera?

A2:The filming began with some of my friends — most of them professional artists — who were already familiar with the idea of performing in front of a camera and comfortable with their own physicality. But because I wanted the project to reflect a wider spectrum of womanhood, I opened a public call, inviting any woman who felt drawn to participate. The response was incredible — women of different ages, appearances, and stories came forward, each carrying her own truth.

Before filming, we spent time together talking openly about what we were creating and why. These conversations built a shared understanding and sense of purpose. I offered some directional notes, but I tried to give as much freedom as possible — to let each woman breathe, move, and express herself naturally.

That process created not only trust but also a deep human connection. What unfolded on camera wasn’t performance — it was presence. It was women meeting each other, and themselves, through the lens.

Q3:The soundtrack — a blend of cello and female vocals — gives the film a warm, full, and hazy texture, almost like a whisper close to the ear. It perfectly complements the film’s tone. Did you and composer Shushan Kerovpyan discuss it a bit beforehand? Could you share any memorable moments from your collaboration?

A3:From the very beginning, I knew I wanted the music to embody the many faces of womanhood — to be earthly and grounded, but also tender, warm, and full of intensity. I wanted it to hold everything together: the passion, the softness, the sadness, the joy, the sensuality — all those contradictions that coexist within us. I’m not a musician, so it was sometimes hard to translate these emotions into words, but I shared my vision with Shushan and offered her a few reference tracks and melodies that inspired me. We met and spoke several times, trying to capture that balance, that emotional landscape that could live alongside the images.

Shushan brought her own world into the sound — elements of her Armenian heritage, including the traditional lullaby that appears in the film. She managed to create a soundtrack that breathes with the images, that feels like another voice among the women.

A moment I particularly treasure from our collaboration was how fluid and organic our process became. Sometimes we would meet at her house or in a café, other times we worked from different places — even from Kythera, sending thoughts and recordings back and forth. There was a deep sense of openness between us. She gave herself completely to the project, and that generosity is something you can feel in every note.

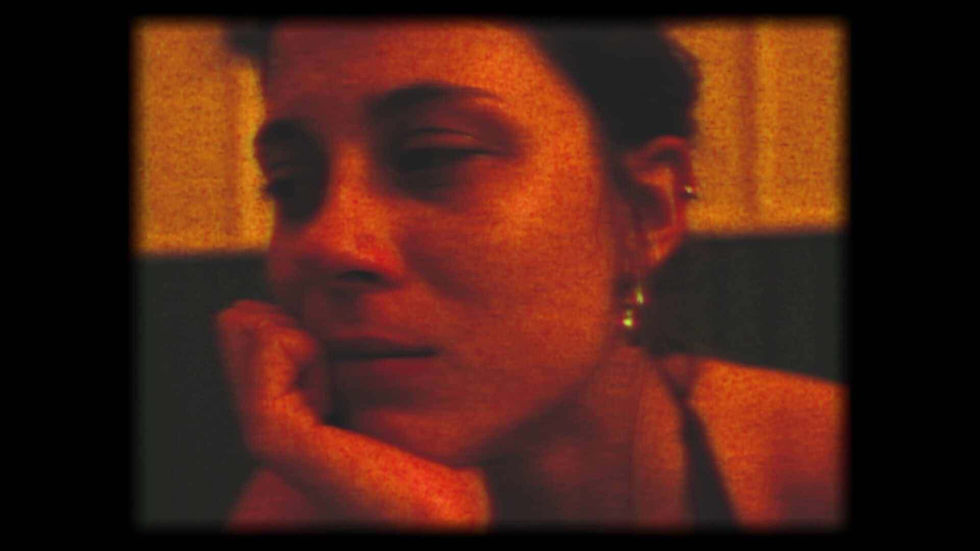

The Land of Wanting More, Marianna Rantou, 2025

Q4:The film addresses themes of sexual abuse, domestic violence, and rape, yet does so through calm, third-person testimonies. It recalls the works of Annie Ernaux, whose writing conveys female humiliation and oppression with a cold, incisive, and quietly unsettling clarity. How do you respond to such literature? Which female thinkers or artists have most shaped your creative sensibility?

A4:It’s a great honor that my work resonates with the writing of Annie Ernaux — to be connected, even in fragility and intimacy, to her clarity and sensitivity is truly humbling. In shaping my creative sensibility, I draw inspiration from a constellation of voices: writers like Colette and George Sand, theorists like Judith Butler, poets like Matsi Hatzilazarou, performers like Carolee Schneemann, cultural critics like Camille Paglia, and the cinematic vision of Sam Shepard in Paris, Texas. Each of these influences, in their own way, has shaped how I approach storytelling — how I observe, reflect, and create spaces for women’s experiences to unfold.

In addressing experiences of abuse, violence, and oppression in the film, I drew not only from research and the stories of others but also from my own lived experiences. My aim was to render these narratives with care, tenderness, and respect — to show their weight without letting them define the women entirely. These stories are real, sometimes painful, but they coexist with resilience, desire, joy, and tenderness. I wanted to honor that coexistence, and to create a narrative that allows both truth and life to breathe together.

Q5:There’s a segment about cutting one’s hair — was that drawn from your own experience? Many today view acts of bodily “transformation” as expressions of autonomy. How do you see it? Is this form of rebellion an act of resistance, or more a private effort to rediscover and reclaim one’s own body?

A5:Yes, the segment about cutting one’s hair was drawn from my own experience. At a moment in my life when things felt particularly heavy, I decided to cut my hair as a way to free myself from the past and from previous experiences that weighed me down. To me, it was a form of rebellion — a private, intimate assertion of autonomy. Acts like these allow us to reclaim our bodies and our selves, to feel more present and alive in our own skin. There’s a profound sense of liberation in choosing, even in small gestures, how we inhabit and transform our own bodies.

Q6:I love the film’s ending — the use of your childhood footage brings a Jonas Mekas–like intimacy, especially in those final lines of “speech” which feel both clever and heartwarming. Could you tell us more about your thoughts behind this choice?

A6:Including my own childhood footage was important to me because I wanted to create a connection across time — between past, present, and perhaps even future — and to trace the fragility and resilience of womanhood from its earliest moments. From the beginning, I was inspired by the intimate, diaristic work of Jonas Mekas, and I wanted this footage to evoke that same closeness and immediacy.

At the same time, juxtaposing these childhood moments with scenes and narratives of abuse creates a tension, a kind of punch in the stomach. It reminds us that these experiences happen to real people, to the vulnerable and innocent. I wanted to hold that reality in the film — to show both the tenderness of early life and the weight of what can happen in the world, so that the audience feels the full spectrum of care, loss, and resilience.

The Land of Wanting More, Marianna Rantou, 2025

Q1:对于女性而言,片名中的“wanting more”可以延伸、解读出很多种意味,根据你日常创作和与人相处的经验,此处最常见的理解是什么?

A1:在我看来,“wanting more”意味着想要更多的自由、更多的温柔、更多的真相。那是一种渴望,渴望能有更多空间去无惧地呼吸、生活,而不必为自己的存在不断道歉。它关乎在生命、爱情、工作、家庭、友情中拥有更多的机会。那是一种被看见、被接纳的愿望——希望能在这个世界伸展自如,不必退缩,不必害怕自己的样子或将成为的人。对我遇到的许多女性而言,“wanting more”并非源于贪求,而是为了夺回那份最简单的权利,也就是以诚实与勇气活着,活得更开阔、更丰盈。

Q2:在短片中,观众可以看到不同年龄段、样貌的女性——甚至有残疾的和裸身的——面对镜头展现日常的生活状态,包括说话、大笑、睡觉、洗澡、自慰等等。这些参与者都是你原先认识的吗?她们加入项目的过程是怎样的?如何取得她们的信任,使其在跟摄像机互动时卸下潜意识的防备?

A2:我在拍摄最初邀请了一些朋友,她们大多是职业艺术家,熟悉如何面对镜头互动、表演,与自己的身体相处。但与此同时,我也希望这部作品能反射出更广阔的女性光谱,因此我发布了一个公开征集,邀请任何有意愿的女性加入,反响出乎意料地热烈——不同年龄、外貌与阅历的女性纷纷报名,每个人都交付了自己真实的模样。

在拍摄前,我们花了很多时间一起交谈,坦诚讨论我们要创作什么,以及创作的动机是什么,这些对话建立了共同的理解与目标感。我给出了一些方向性的提示,但更多时候选择放手,让每位女性以最自然的方式呼吸、行动、表达。

这样的过程不仅建立了信任,还创造出深刻的人际连接。摄影机前所展开的并非“表演”,而是一种“呈现”,这是女性与女性之间、也是女性与自我之间的相遇。

Q3:我想聊一聊片中的配乐,大提琴和女声吟唱的融入为作品增添了温润、饱满、朦胧的质地,就好像有人在近处耳语,也和影片整体的风格基调很接近。你和负责配乐的Shushan Kerovpyan有事先沟通过吗?可否分享下合作中让你感受深刻的细节?

A3:从创作伊始,我就希望配乐能勾勒出“女性”的多重面貌——既脚踏实地,又温柔、饱满且充满张力。我希望它能包容一切的激情与柔软、悲伤与喜悦、感性与理智……那些交织在我们体内的矛盾。我并非职业的音乐人,因此有时难以用语言准确传达这些感受。我跟作曲家 Shushan Kerovpyan分享了自己的想法,也找了些参考曲目发给她。我们多次见面讨论,努力捕捉那种平衡,一种能与影像共存的情感景观。

Shushan 将自身的经历融入到了音乐中,包括她亚美尼亚血统的元素,片中出现的那首摇篮曲便源于此。她创作出的配乐能和影像共呼吸,仿佛一个从女性群体内部发出的声音。

很难忘的是,我们的合作过程极其顺利和流畅,我们有时在她家、在咖啡馆见面,有时远程联系。她住在基西拉岛(Kythera),我们互相发送自己的想法和录音。那是一种很开放的氛围,她全然投入其中,你能从每个音符中感受到她慷慨的给予。

The Land of Wanting More, Marianna Rantou, 2025

Q4:影片中涉及到了性虐待、家庭暴力和强奸等话题,但却是借由平静、第三人称证词的视角来传达,让人想到安妮·埃尔诺(Annie Ernaux)的小说,同样也是以冷酷、尖锐和让人隐隐不适的笔调,来描绘加诸女性身上的屈辱和压迫。你在阅读这类文学作品时的感受是怎样的?在创作过程中,你都受到过哪些女性思想家、艺术家的启迪?

A4:我的作品能被拿来跟安妮·埃尔诺(Annie Ernaux)的写作相对比,于我是莫大的荣幸。她那种冷静、细腻的敏感度总能令我深受触动。我在创作上的感受力,脱胎于这样一个声音的星丛:以柯莱特(Colette)、乔治·桑(George Sand)为首的作家,以朱迪斯·巴特勒(Judith Butler)为首的理论学者,以玛茜·哈齐拉扎鲁(Matsi Hatzilazarou)为首的诗人,行为艺术家卡洛琳·史妮曼(Carolee Schneemann),文化评论家卡米拉·帕格利亚(Camille Paglia),以及《德州巴黎》中山姆·夏普德(Sam Shepard)描绘的影像诗意。他们共同影响了我的叙事观和讲故事的手法,包括如何去观察、去反思,如何为女性经验创造出剖白的空间。

在处理性侵、家庭暴力、压迫等题材时,我不仅参考了他人的故事与研究,也从自身经历中汲取了一些内容。我的目标是以温柔与敬畏的方式呈现这些重量,同时避免让它们成为女性身份全部的定义。这些故事是真实的、痛楚的,但与之共存的还有坚韧、欲望、喜悦与温情。我希望借这部作品,让“真相”与“生命”在同一空间内呼吸。

Q5:影片中有一段剪短发的自述,是完全取材于你的个人经历吗?在如今很多人看来,对身体进行“改造”的行为,代表了一种主权意识。能谈谈你对此的看法吗?我们的“叛逆”究竟是为了抗争,还是更多服务于某种私密的、重新了解和掌控自己身体的欲望?

A5:是的,剪发这段来自于我亲身的经历。那是生命中一个格外沉重的时刻,我决定剪去长发,仿佛在跟过去那些令我窒息的经历告别。对我而言,这是一种反叛的姿态,也是私密而自主的宣言。类似的行为,让我们重新夺回对身体与自我的掌控,得以再次感受到“存在”的份量。哪怕只是一个微小的动作,也能让人重新感到鲜活。它关乎选择——选择如何扎根在自己的身体里,如何唤醒自我,这种行为本身就充满着解放的力量。

Q6:我喜欢这支作品的结尾!用了你自己童年时的素材,渲染出一种乔纳斯·梅卡斯(Jonas Mekas)式的家庭“私影像”特征,尤其是最后那几句“演讲”,非常机灵和让人动容。能跟我们分享下背后的考虑吗?

A6:之所以在片尾加入自己的童年影像,是因为我想建立一种连接——在过去、现在、甚至未来之间,从源头开始,追溯女性的脆弱与坚韧。在拍片时,我深受乔纳斯·梅卡斯(Jonas Mekas)私人日记式影像的启发,希望这些片段能唤起类似的亲密与即时感。

同时,将童年与关于暴力与创伤的叙述和画面并置,所迸发出的张力近乎令人心碎,它提醒我们这些经历并非抽象的,而是发生在真实的、脆弱而天真无辜的个体身上。我希望借由这种对比,展现出生命完整的面貌:幼年的温柔与生命之重,让观众同时感受到关怀、失落与重生的力量。

▌more information: https://www.bisff.co/selection/the-land-of-wanting-more