BISFF2025 | Correspondence 通信计划058:The Gods (الالهة) 众神

- BISFF

- 27分钟前

- 讀畢需時 7 分鐘

BISFF Correspondence 通信计划

This program involves conducting brief email interviews with the directors of the international films featured in the festival, in lieu of the traditional Q&A session that follows the screenings. Through this program, we hope to provide a platform for filmmakers to discuss their work and share their insights with our audience in China.

为了跨越种种障碍,开辟更多交流空间,我们设置了“BISFF Correspondence 通信计划”,对部分国际单元的参展作者进行系列访谈,这些访谈将在作品放映后发布在联展各个媒体平台。

The Gods (الالهة)|众神

Anas Sareen 阿纳斯·赛任

2025|0:15:00|Switzerland|Arabic, French|Asian Premiere

Director: Anas Sareen

Interviewer & Translator: Ruth. C. Zhang

Coordinator & Editor: Suliko

导演:阿纳斯·赛任

采访、翻译:张超群

统筹、编辑:苏丽珂

Q1: Your film is titled The Gods, yet it contains no explicit religious iconography. Instead, it feels like a secular mythology that the two brothers construct in the absence of their father. Why did you choose this title? And where does “godliness” in this film originate—from the father, from nature, from the body, or from the boys’ own grief?

A: From my mother, actually. She used to read me stories from the Quran, full of prophets, winged horses, and other celestial beings. My imagination started there, and I remember trying to represent God to myself, and coming up with various hazy iterations of what his face might look like… In the film, as you say, this reglious origin gives rise to a secular mythology, and a cinematic poetry, that moves from sky to earth to first speak of grief, then to help heal it.

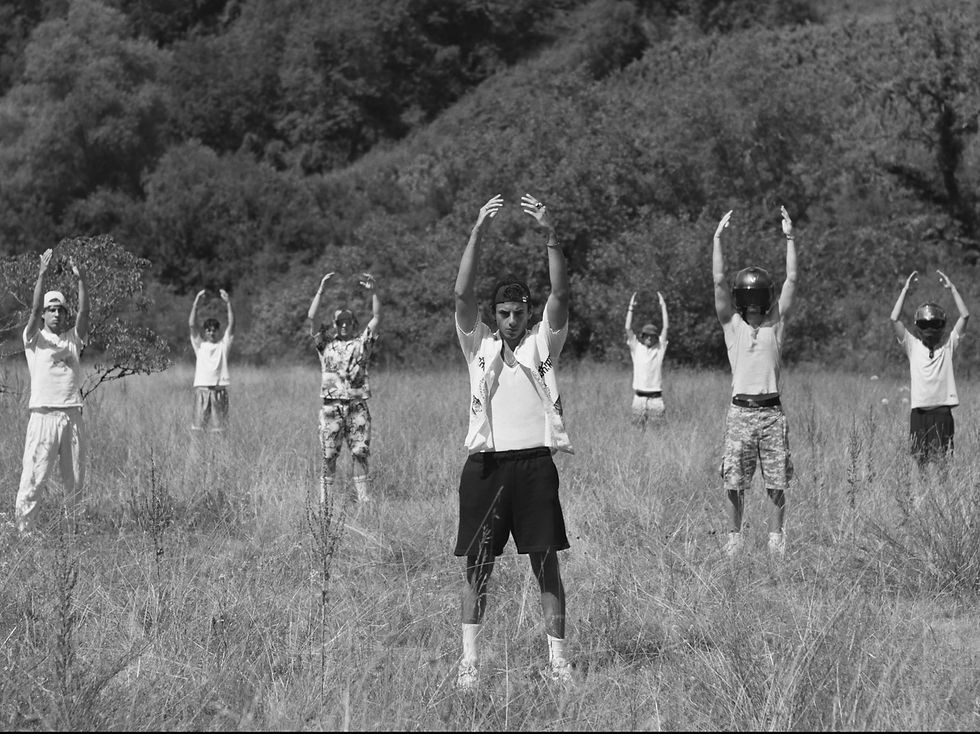

The Gods (الالهة), Anas Sareen, 2025

Q2: The father’s dancing, Moïse’s raised-arm movement in the field, and even the synchronized gestures of the boys in the wide shot all have a ritualistic quality. How do you see the role of the body in this film? Do these movements form a kind of familial ritual language—something inherited from the father yet re-invented by the brothers?

A: It is a fleeting image, but one of the earliest memories is of my father dancing in our living room. It came to represent the core of what I wanted to say in the film, both about men and about my own Arabic identity. There are memories within us, within our bodies, that we can call on in moments of hardship and that help us reimagine ourselves anew. To me, dance is the ultimate act of freedom. It has the power to cast fear and shame aside, to help us be fully ourselves. This is what the father transmits to his sons from beyond the grave, and his dance starts with a prayer- like gesture before becoming a liberating flow of movement. The whole story, the plot, is written through bodies in the film. Whether it be the father, the brothers, or the friends in the field, reading the bodies tells you all you need to know.

Q3: The film opens with a glaring white sun, but later a “black sun” appears as Moïse wanders away. It feels like a celestial metaphor—a cosmic tear that mirrors the process of grieving. What psychological or spiritual meaning did you hope the black sun would carry?

A: The perceptiveness of your question is already a beautiful answer. People should trust their own instincts when it comes to poetry…

Q4: In the superimposed shots of the forest and the boys’ faces, the branches lie over the skin like veins—suggesting both nature and memory. Why did you choose superimposition to convey their emotional and spiritual states? For you, is superimposition a kind of foggy fusion, or is it a sharper, more “soul-level” form of imagery?

A: There is indeed something soulful to me about the superimpositions… I think they help me convey a deeper truth about the characters, their inner lives, in a way that is purely cinematic. I reworked the entire film with those images in mind once I had understood their value: they allow the story to move between worlds, between the living and the dead, the natural and the human, the real and the imaginary… I will probably make use of superimpositions again; a kind of grace comes once you trust the medium of cinema entirely.

Q5: Throughout the film, the brothers almost never truly share the same physical space, until the final wide shot where they meet again. Was this spatial separation intended to mirror their internal split? And does their final encounter represent a form of reconciliation that goes beyond dialogue?

A: I have a complex, even difficult, relationship with my brother. Love necessairly takes place at a distance between us. It is a real and deep love, but one that, like in the film, is largely wordless. Or yes, beyond words. That reality became a core principle during the writing and editing, and I arranged the story, and the bodies within it, in a dance of proximity and distance, a geometry of love. It remains the most fascinating question to me – what is love? Everything I write seems to begin and end there…

Q1: 影片名为《众神》,但片中并没有明确的宗教符号。更像是兄弟俩在父亲缺席后,各自创造的一套私人神话。请问您为何以“神”命名?在您看来,这部影片中的“神性”究竟来自哪里:父亲、自然、身体,还是孩子们各自的痛苦?

A: 其实,神性来自我的母亲。她曾给我读《古兰经》里的故事,那里充满了先知、有翼的马,以及各种天界的存在。我的想象力正是从那里开始的。我记得自己曾试着在脑海中“呈现”上帝,反复构想祂的面孔会是什么样子,最终只留下了一些模糊而飘忽的形象。在这部电影中,正如你所说,这种宗教性的起源转化为一种世俗的神话,以及一种电影的诗性:影像从天空落向大地,先是诉说哀悼,随后又尝试促成疗愈。

Q2: 父亲的跳舞、莫伊斯(Moïse)在田野中举起手臂的动作,以及远景里一群少年同步举臂的场景,都带有强烈的仪式感。您如何看待“身体”在这部电影中的作用?这些动作是否构成了一种继承自父亲、又被兄弟重新发明的家庭仪式语言?

The Gods (الالهة), Anas Sareen, 2025

A:这是个短暂的画面,但却是我最早的记忆之一:我的父亲在客厅里跳舞。

这个画面逐渐成为我在影片中想要表达的一切的核心,无论是关于男性,还是关于我自身的阿拉伯身份。我们身体里储存着记忆,有些记忆潜藏在我们自身之中,在艰难的时刻被唤醒,帮助我们重新想象自己。对我来说,舞蹈是一种终极的自由行为。它能够驱散恐惧与羞耻,让我们得以完整地成为自己。这正是父亲在死后传递给儿子的东西。他的舞蹈以一种近乎祈祷的姿态开始,随后转化为一种解放性的流动。整部影片的故事情节其实是通过身体来书写的。无论是父亲、兄弟,还是田野中的朋友,只要你去“阅读”这些身体,你就已经理解了一切。

Q3:影片以刺眼的白色太阳开场,却在莫伊斯出走时出现了一个“黑太阳”。这几乎像是一场天文隐喻,将哀悼具象为一种宇宙的裂缝。您在构思“黑太阳”时,希望它承载怎样的心理、情绪或精神象征?

A:你这个问题本身很敏锐,这已经是一种美丽的回答了。我认为,在面对诗意的时候,人们应该相信自己的直觉……

Q4: 森林与面部的叠印镜头中,树枝像血管一样覆盖在皮肤上,既是自然,也是记忆。您为何选择用叠印来表现兄弟的情感与精神状态?叠印对您来说,是一种迷雾般的混合,还是一种更锐利、更接近灵魂层面的视觉表达?

A:对我来说,叠印确实具有灵魂层面的质感。我认为它们能以一种纯粹电影性的方式,帮助我传达人物更深层的真实,即他们的内在生活。当我真正理解这些影像的价值之后,我几乎是围绕着它们重新构建了整部影片。叠印使故事能够在不同世界之间穿行:生者与死者之间、自然与人类之间、现实与想象之间。我大概还会再次使用叠印。当你完全信任电影这种媒介时,一种恩典便会出现。

The Gods (الالهة), Anas Sareen, 2025

Q5:影片中兄弟几乎从未真正共享同一个空间,直到结尾那段远景的相遇。您是否有意用这种空间上的分离来表现他们内心的分裂?而他们最终相遇的那一刻,是否意味着一种超越语言的和解方式?

A:我和我的兄弟之间有着一段复杂,甚至可以说是艰难的关系。爱,必然在我们之间以某种距离的形式存在。那是一种真实而深刻的爱,但就像电影中呈现的那样,它在很大程度上是无言的,或者说是超越语言的。这种现实在写作与剪辑过程中逐渐成为一个核心原则。我据此安排了故事,也安排了其中的身体:在亲近与疏离之间舞动,构成一种爱的几何学。对我而言,这仍然是最迷人的问题——什么是爱?我写下的一切,似乎都从这里开始,也在这里结束。

About the Artist 艺术家简介

Born in 1992 in Dubai to an Iraqi-Turkish mother and an Indian father, Anas studied literature and film history at the universities of Lausanne and Oxford, before working as a screenwriter and director. He is a feature-film programmer for Berlinale Generation and a regular contributor to the magazine Talking Shorts. He has just completed his short film, THE GODS (LES DIEUX - (الالهة)), and has begun writing a first feature, titled SWANSONG.

阿纳斯(Anas)1992年出生于迪拜,母亲为伊拉克-土耳其人,父亲为印度人。他曾在洛桑大学和牛津大学学习文学与电影史,随后从事编剧和导演工作。他是柏林国际电影节新生代(Generation)单元的长片选片人,同时也是 Talking Shorts 杂志的常驻撰稿人。他刚完成短片《众神》(The Gods / Les Dieux / الالهة),并已开始创作首部长片剧本,片名为《天鹅之歌》(Swansong)。